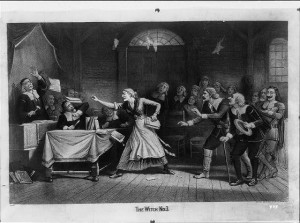

As her symptoms intensified – she fell into violent fits, complained of being strangled, and attempted to throw herself into the fire – Reverend Willard observed that she began to “carry herself in a strange and unwonted manner,” saw apparitions, and experienced violent “fits” over a period of three months.

In the midst of one fit, she spoke in a “hollow” voice, and called the minister “a great black rogue” who “tell[s] the people a company of lies.” Willard answered back, “Satan, thou art a liar and a deceiver, and God will vindicate His own truth one day.” Others in the room took up the confrontation, telling the Devil that “God had him in chains.”

The answer came back, “For all my chain, I can knock thee in the head when I please.” Meanwhile, in her own voice Elizabeth told how the Devil had promised to make her a “witch” if she would sign a “compact” to become his servant.

Under pressure to reveal the “true and real occasion” of her fits, Elizabeth admitted that the Devil had frequently appeared before her in the past three years and offered her “money, silks, fine clothes, ease from her labor” and other items of youthful fancy, particularly on her walks from the Willard home to her parents after work in the evening. These meetings had been infrequent at first, but had become a daily occurrence.

From the Puritan perspective, Elizabeth Knapp’s possession was the result of her discontent with her condition, with her place in the social order. Had she been willing to be content with her lack of financial resources, with her work as a servant, and with her limited horizons, she would not have become possessed.

It was the same sin that defined other women as witches, and the one that led Elizabeth at times to see herself as a witch. She admitted that the Devil came because of her unhappiness with her station in life, and that he came more frequently once she started to work as a servant in the Willard household, a household much more prosperous than her own.

But for Puritans, possession was not witchcraft, but the potential for witchcraft. Ministers could prevent the onset of witchcraft by helping the possessed adjust to their place in society. In Elizabeth’s case, the Devil was able to take advantage of her discontent by attracting her with the things she most desired and leading her to think about committing other sins identified with witches, but he was not able to win her completely.

Events in Groton proceeded from the assumption that Satan lures certain people into compact with him, promising them, as he promised Elizabeth Knapp, that all “should be well,” and they need not worry any longer about sin and salvation. The people of Groton also believed that, in the full course of God’s providence, good would overcome evil.

As the story of Elizabeth Knapp reveals, some tensions originated in the religious expectations of Puritanism. One expectation was that believers fulfill, to the best of their ability, their moral duties. Another was that they examine their motives to see whether they had sufficiently repented of sin and trusted entirely in the mercy of Christ.

The Reverend Willard. When not possessed, Elizabeth was respectful of the man who was both her minister and master. When the demons were in her, however, she expressed an intense hostility toward him. She railed at him and called him a liar. She castigated her father and others for listening to him. She challenged his authority in the community and his power over her.

She had cause to resent him. He was a young, well-off, Harvard-educated minister whose life was full of promise. She was a young woman with little schooling and little prospect of anything but service to others, either as a servant, a daughter, or a wife.

He spent most of his time reading, writing, and traveling. She had never been taught to write, seldom left Groton, and spent her time sweeping his house, caring for his children, carrying in his wood, keeping his fires burning – all so he could continue to work in peace and comfort.

Accustomed to Confession: Puritans practiced the ritual of confession, and confession became crucial to witch-hunting. To confess was to make visible the hidden sin that lurked in everyone. This was a crucial step. When men and women joined the church in early New England, they were asked to confess their sins.

The magistrates and ministers who questioned the accused witches asked them to reveal their hidden allegiance to Satan. Because Puritans felt heavily the weight of their sin, and because confession was an integral part of their lives, it’s not surprising that some fifty men and women confessed to having made a pact with the Devil.

The Puritans believed that God had entered into a special relationship with godly people. This relationship obliged them to purge themselves of sins that inevitably accumulated. The ministers and magistrates in New England believed witch hunting, and the public executions of witches cleansed the community of evil.

Witch-hunting was not unique to Puritan America. It occurred in both Catholic and Protestant regions of Europe, and the toll it exacted in New England was much smaller than in Scotland or parts of France and Germany. Why witch-hunting became deadly in some Puritan villages but not others will likely remain a mystery.

Elizabeth Knapp wasn’t a witch. She married Samuel Scripture and lived out her life as a good Puritan wife and mother. So successfully did she obliterate her discontent that she almost completely disappears from the public records after 1673.

Huntington’s Chorea. Modern medicine has cast an interesting light on part of this story. It now appears that Elizabeth most likely was afflicted with adult onset Chorea, also known as Huntington’s disease, a rare dominant genetic disorder that takes its name from the Greek word for dancer. Eight people in every 100,000 in Europe and North America suffer from it.

The disease causes the selective deterioration of certain movement related structures deep inside the brain. The symptoms of the disease, which may first appear around puberty, include excessive, spontaneous, irregular movements of the limb that flow from one part of the body to the other that worsen over time, sometimes leading to neurological deterioration including apathy, irritability, memory loss, manic depression, and schizophrenia.

Sleep is usually the only time when a choric is not vulnerable to fits. There is currently no cure, but antipsychotic medications may lessen the symptoms. Bearers invariably die 10 to 25 years after the onset. They have been called everything from saints to witches since the sixteenth century.

SOURCES

Witch Hunting in Salem

Devils in the Root Cellar

Groton in the Witchcraft Times

The Possession of Elizabeth Knapp